The Miami Herald

Written by Ashley Miznazi

At barn No. 5 at the Larson Dairy farm just north of Lake Okeechobee, a line of cows pump out milk bound for grocery stores shelves and family refrigerators across Florida. Being cows, they are also producing a steady supply of something else — manure, a lot of it. Poop is an inevitable byproduct of the cattle industry and, like cow burps and farts, it emits methane, a potent greenhouse gas that scientists point to as a major driver of climate change. But an innovative process now in operation at Larson helps reduce the climate impact of this dairy herd, capturing and cleaning methane locked in those cowpies and sending it to a natural gas pipeline near the farm.

Environmentalists and climate change experts, who have long criticized the cattle industry over pollution problems, have plenty of questions and concerns about the process. But the end result is something that Jacob Larson, a third-generation Florida farmer, sees as a big step forward he could not imagine possible a few years ago: His dairy waste supplements the state’s energy supply and can perhaps even become a valuable product of its own.

“Just the thought process of turning manure into fuel is mind-boggling,” said Larson, during a tour of the dairy’s poop-to-power system, which emerged through a partnership with Brightmark, a waste-to-energy company based in California that has picked up much of the tab for installing and operating the equipment.

TURNING POOP INTO POWER

Since the source of this power is cow poop, the process itself is not particularly pretty. In the dairy barn, a spray system regularly wets down the manure with water to liquefy it, creating a brown stream that flows down a ditch into a concrete reservoir. From there, pipes take it into the heart of the system, something called an “anaerobic digester” lagoon. The system appears relatively low-tech. From above, a digester consists of large black tarps spread over what looks like a mound. But underneath, it functions like an insulated, oxygen-free underground bunker. Manure goes through four chemical reactions as bacteria feed on it. Depending on the temperature and amount of nutrients in the manure, Brightmark says it can take days to weeks for “bio-gas” to form, cleaned, and processed. The company delivered its first bio-gas to a nearby pipeline in August.

Anaerobic digesters are in place on four of Larson’s sprawling farms, fed by a steady supply of manure from some 12,000 cows. The poop-to-power calculation is complicated but by one expert estimate, 10 of the cows at barn No. 5 can produce enough bio-gas in a month to run a typical home over the same period. “The Larsons take care of cows and produce high-quality cows and high-quality manure,” Larson said. “We commit our manure supply to Brightmark, and they take the manure supply from there.”

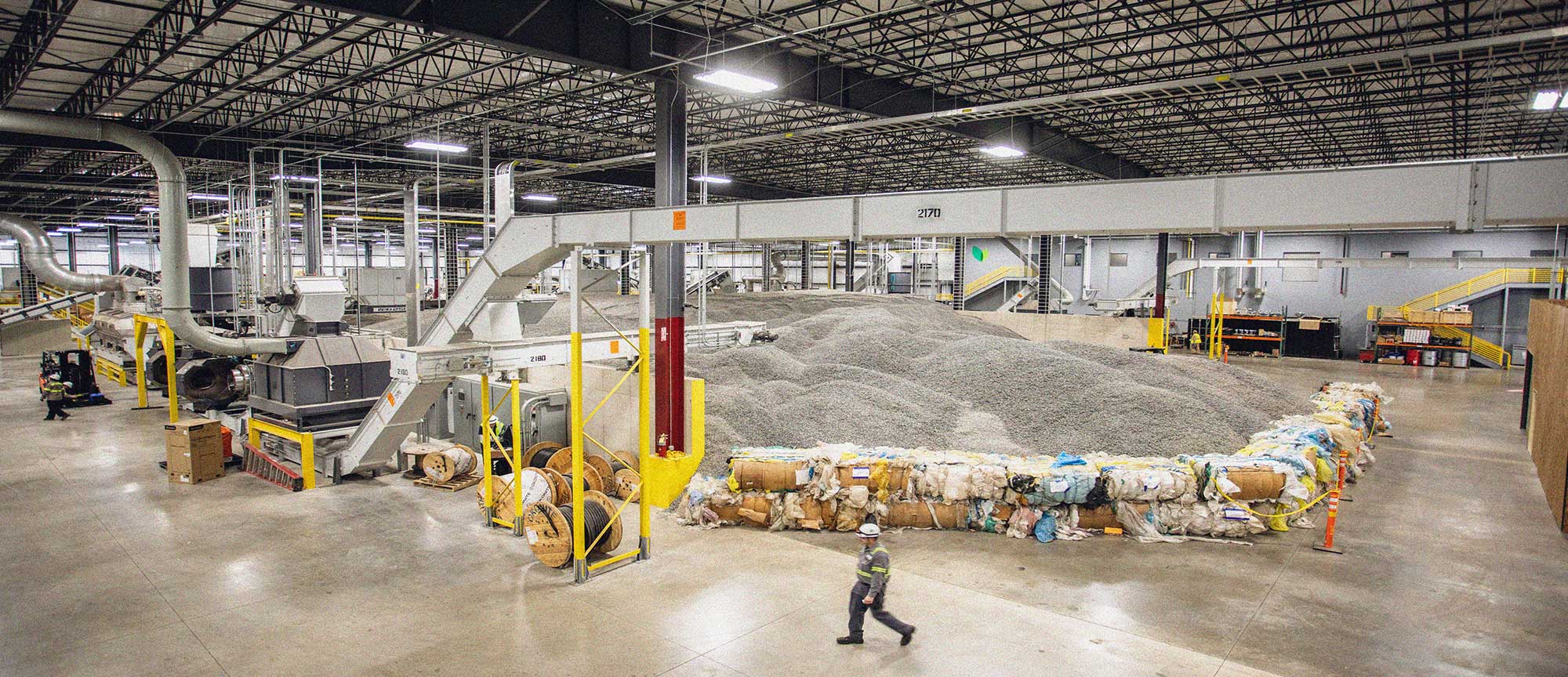

After processing, what’s left of the manure is run through a rotating composter that squeezes out water and remaining solids. The dried leftovers, stored in piles, and the remaining liquid are used as fertilizer on the farm. “It’s like recycling, that’s the beauty,” said Rishi Prasad, an environmental science professor at Auburn University who is not affiliated with Brightmark but has studied the process involved. “You are basically recycling manure on the farm for energy, for feeding the plants like corn, and then that corn would go back to feeding the dairy cows.”

THE METHANE CHALLENGE

Livestock operations, according to a United Nations assessment, account for about a third of all global methane emissions — with cows far and away the No. 1 source. Methane is a particularly problematic greenhouse gas — its warming effect is some 28 times greater than carbon dioxide on a 100-year timescale, and more than 80 times more powerful over 20 years, according to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

So reducing methane emissions could make a big difference and is one of the major challenges of curbing climate change. While some activists call for banning or shrinking the cattle industry, that goal hasn’t won much political or public support. “The whole planet is not going to stop eating beef, or stop drinking milk or stop eating pizzas,” said Prasad, who studied anaerobic digesters as part of his Ph.D. research at the University of Florida. “But we need to think about how we can make the food production industry more sustainable and reduce emissions so we can buy more time.”

California, where Brightmark is based, already has embraced the use of digesters and fueled expansion through a state policy called the Low Carbon Fuel Standard (LCFS) intended to reduce the impact of transportation fuels. Under the complex rules, California views digesters as “carbon-negative” so bio-fuel can be used as a “credit” to balance out fossil fuels in a commercial trading market. It works this way. While there are no caps on emissions from dairy farms, oil and gas companies have strict limits on emissions produced by transportation fuel. To stay within emissions limits, those companies can either sell fuel with a lower carbon footprint or offset its use.

So at dairy farms, owners of the digesters can sell “carbon-negative” fuel to oil and gas companies like Chevron, which partnered with Brightmark — a transaction that helps offset its own emissions in the California system. Because digesters receive credit both for reducing methane emissions from manure and replacing a fossil fuel, dairy bio-gas is a particularly attractive commodity in the California market, 10 times more valuable than landfill gas.

Brightmark sees a promising future in Florida, where digesters also have been catching on. According to EPA’s database, as of May 2022, there were about 330 anaerobic digesters at livestock farms in the U.S. and over 30 in Florida. Larson Family Farms isn’t included on the list yet. The EPA also sees room for growth in Florida, with one report projecting up to 80 dairy farms as candidates. “The mission for us is to re-imagine waste and really look at better ways to create environmental benefits associated with the things that we waste,” Bob Powell, CEO of Brightmark, said in an interview with the Miami Herald. “I definitely think the project with the Larsons is a flagship project and one that people can point to.”

Brightmark, Larson, and other supporters see the systems as a win-win. Bio-gas creates a new use, and potential revenue stream, from a former waste product. “We’re going to be offsetting on an annual basis 57,000 tons of CO2 equivalent out of the environment,” Powell said. “And to put that in perspective, that would be the equivalent of planting over 75,000 acres of forest each year.”

For more information on Brightmark’s renewable natural gas projects, please visit here.